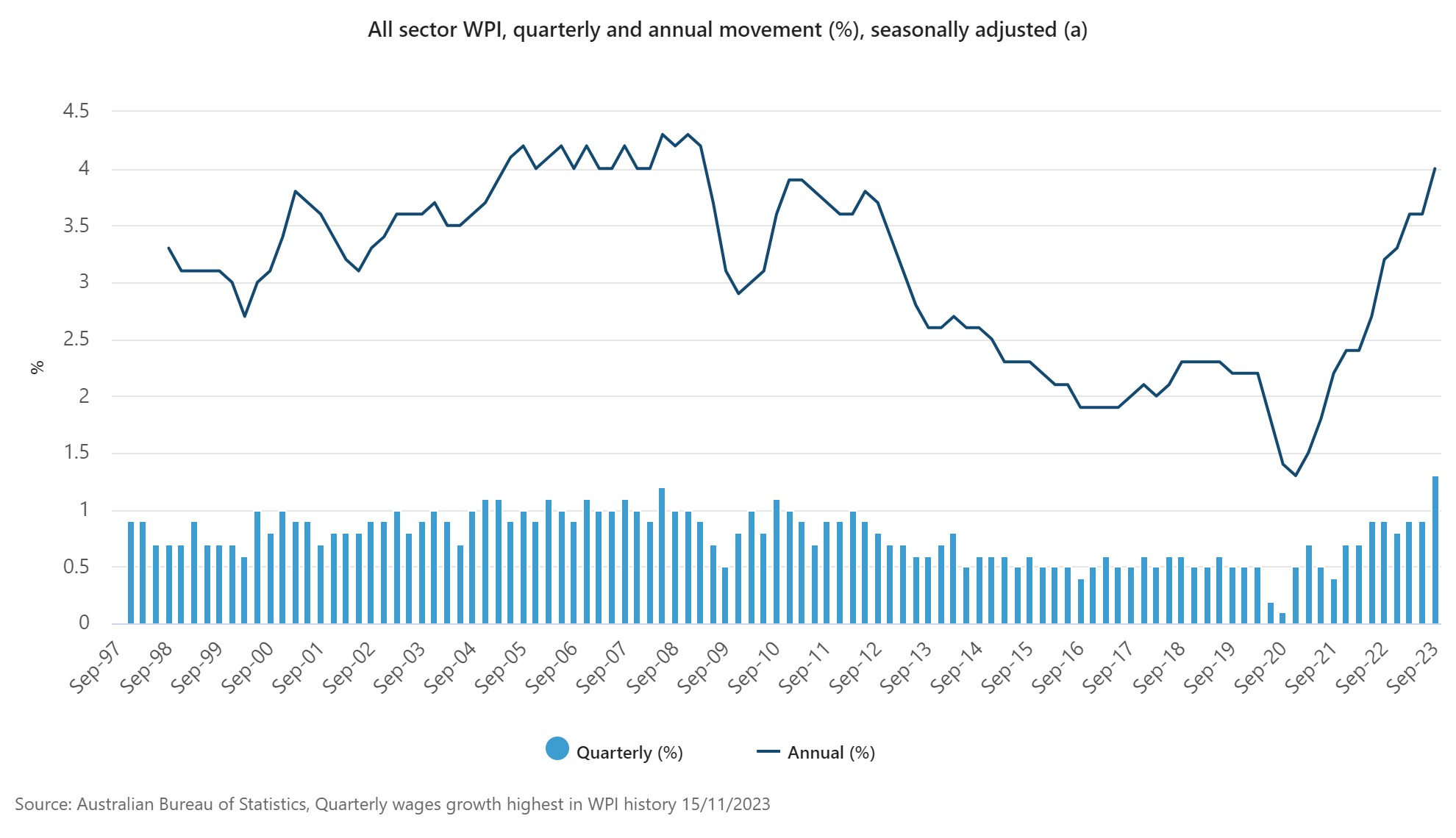

The latest quarterly growth of the Wage Price Index (WPI) was the highest in its 26-year history, according to the ABS, rising +1.3% for the September quarter.

From an annual growth perspective, the +4.0% growth was the highest since the March quarter of 2009.

Michelle Marquardt (pictured above left), ABS head of prices statistics, said a “combination of factors” led to widespread increases in average hourly wages this quarter – most notably the 5.75% increase of the minimum wage affecting potentially millions of private sector workers.

Other private sector factors included the application of the Aged Care Work Value case, labour market pressure, and CPI rises being factored into wage and salary review decisions.

“The public sector was affected by the removal of state wage caps and new enterprise agreements coming into effect following the finalisation of various bargaining rounds,” Marquardt said.

Wage growth increased this quarter across each of the different methods that set pay.

Jobs paid by individual arrangements were the main driver of wage growth, with award and enterprise agreement jobs also contributing more to wages growth than historically seen in a September quarter.

While some may baulk at the record figures and what this could mean for the Australian economy, Todd Sarris, managing partner at mortgage advisory firm Spartan Partners, said it’s essential to place it in proper context.

“The latest result is ultimately the outcome of several very unique forces at play that were never present all together in prior historical periods,” said Sarris (pictured above right).

“This recent WPI run of form is the result of prior instances of closed domestic and international borders associated with Covid that caused immense economic uncertainty to which businesses pivoted by holding back on wage growth.”

For example, the September 2020 quarterly WPI for instance only registered +0.1%.

Once domestic and international borders reopened and businesses regained confidence, Sarris said the labour market reacted by significantly tightening.

“Bargaining power thus gravitated away from the employer and to the employee. Throw in an explosion in inflation and employees justifiably requested wage growth such that it:

Furthermore, the RBA saw this coming, projecting a 4% annual WPI growth in its November 2023 RBA Statement on Monetary Policy.

“Wage growth is genuinely good for the economy as it supports discretionary spending,” said Sarris.

“It supports job creation and provides business with confidence to undertake future capital expenditure that then - in a circular fashion - supports job creation, supports wage growth, and supports discretionary spending.”

Video above shows Stephen Koukoulas’ - economist and managing director of Market Economics - two minute take on the Wage Price Index (WPI).

While wage increases are generally positive for the economy, Sarris said it can lead to wage-led inflation spirals if conditions aren’t checked.

“This situation can get scary quickly,” said Sarris.

Generally, a wage-led inflation spiral occurs through four stages:

While initially this could lead to economic growth and increased wages, it could lead to economic instability and higher prices over a sustained period.

Sarris said the RBA may be forced to act if there was a situation where strong wage growth outpaces inflation.

“They absolutely want to avoid a situation where supply shock inflation then leads straight into a wage led upward price spiral.”

While the term ‘wage-led inflation spiral’ certainly sounds scary, could this happen in Australia under the current conditions?

Two elements that drive increases in the WPI are the proportion of jobs that have a wage increase and the size of the increases received.

In original terms, across all public and private sector jobs that had a wage movement in the September quarter, the average change was a 5.4% increase, up from 4.0% in September quarter 2022, according to Marquardt.

“The growth was mostly driven by increases to wages in the private sector. Almost half (49%) of all private sector jobs recorded a movement with the average increase being around 5.8%.”

This compared to the public sector where 34% of jobs recorded an average pay rise of 3.3%.

Sarris said he remained “very cautious” that wage growth may continue to have further upside potential as multi-employer bargaining has “only just started”.

Sarris cited the recent decision by the Fair Work Commission, which allowed the United Workers Union to bargain for pay rises up to 25% across multiple employers.

“This decision, the first order of its kind under federal Labor’s new industrial relation laws, means 64 employers and 12,000 educators will be able to collectively bargain for a pay rise,” Sarris said.

“Any strong positive outcome will be the catalyst for others to follow. Headline inflation in Australia still sits at +5.4% but it’s reasonable for a union to still fight to net out as much as possible.”

With respect to Australian property, Sarris strong WPI outcomes are generally supportive of property prices.

“This is because it perpetuates the aforementioned cycle: wage growth supports discretionary spending, which preserves jobs, which instils confidence in businesses to invest, which in turn preserves jobs, which supports discretionary spending and on and on,” said Sarris.

Then you have the other dynamic at play – if a lot of people are employed and their wages a growing, there is a fair chance that consumers are making their loan repayments.

“If incidences of loan arrears are low, it means that there is less of a chance that surplus property stock (foreclosures) will hit the market,” Sarris said. “Thus, providing a chance that demand will surpass supply through low unemployment, wage growth, and strong net migration.

“The other benefit of low loan arrears is that banks will maintain their relatively accommodating credit underwriting standards and thus also preserve property demand.”

But again, the effects of how long that environment would last if a wage-led inflation spiral occurred remains to be seen.

Do you think wage growth is good for the Australian economy? Or is it fuelling a wage-led inflation spiral? Comment below.