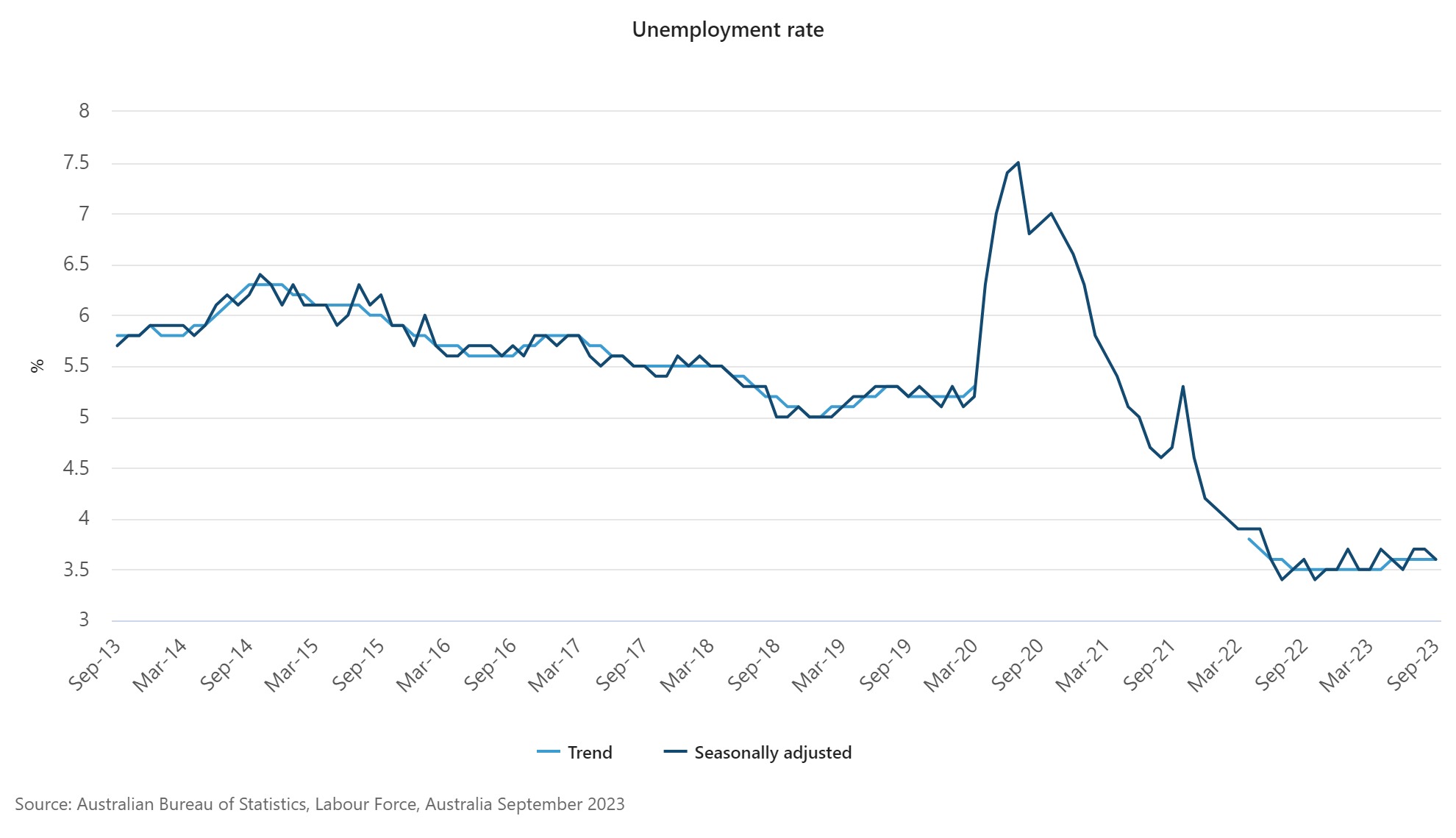

The latest unemployment figures came as a surprise to many last week with it falling 0.1 percentage point to 3.6% in September, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

However, a mortgage adviser has urged people to take a wider view when looking at these figures given the influence pandemic-induced policy has had on the market.

Todd Sarris (pictured above left), managing partner at mortgage advisory firm Spartan Partners, said Australians “must remain vigilant” when consuming economic information and need to take year-on-year or quarterly comparisons with a pinch of salt.

“It always pays to zoom out and compare with pre-COVID periods,” Sarris said. “COVID of 2020-22 was a once in a generation event that created one-off experiences that will not repeat in the short to medium term all things being equal.”

The ABS was quick to temper expectations when it released its latest unemployment figures last Thursday.

While employment increased (+7,000 people) and unemployment decreased (-20,000 people), the fall in unemployment also reflected a higher proportion of people moving from being unemployed to not in the labour force.

This is called the participation rate, which measures the number of people employed or looking for a job, meaning that some unemployed people have stopped looking for work.

However, the participation rate only saw a slight decrease coming off record highs.

“It is important to remember that a fall in unemployment does not always mean much higher employment,” said ABS head of statistics Kate Lamb. “Looking over the past two months, average monthly employment growth was 35,000 people, around the average growth we’ve seen in the past year.”

“In trend terms, the growth in employment has gradually slowed, however the employment-to-population ratio and participation rates are still close to their recent record highs. These still point to a tight labour market.”

This tight labour market echoes the “narrow path” that former RBA governor Philip Lowe had envisioned the central bank must tread, essentially aiming to bring inflation back to its 2% to 3% band without causing a recession and mass unemployment.

“(The RBA) has sought to do this while also preserving as many of the gains in the labour market as possible, with the unemployment rate at a near 50-year low during 2022/23,” Lowe said in the RBA’s recent annual report.

Current RBA governor Michele Bullock reflected on this during a fireside chat in October.

“We’re trying to bring inflation back down in a reasonable amount of time while preserving employment gains, by not really bringing the economy to its knees so that lots of people get unemployed,” said Bullock (pictured above right).

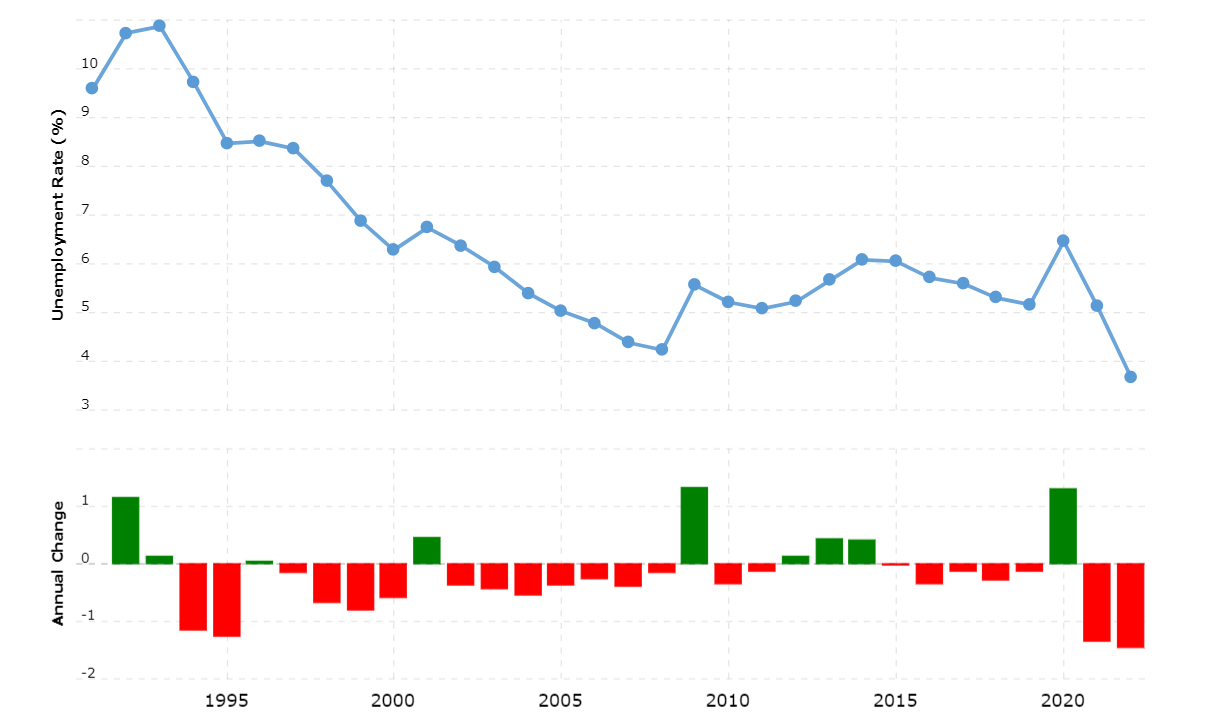

Despite the RBA’s intentions, Sarris said the unemployment rate was more likely to go back up to its historical average since the current environment was “not normal”.

Australia's unemployment rate averaged between 5% and 6% over the last 10 years and 6.53% between 1992-2022.

Sarris said these prior periods had open borders, more normal RBA rate levels, and normal fiscal policy spend. This was unlike the lockdowns, closed domestic and international borders, cash rate near zero cash rate, and government cash handouts that categorised the pandemic era.

Sarris said “ridiculously low” unemployment levels – like we have now – are a bit like breaking an entrenched personal bad habit.

“Sure, you may have seen something trending on social media that spurred action to tackle the bad habit, but unless you maintain that action repeatedly for an extended period of time, you naturally revert back to the entrenched bad habit,” Sarris said.

"It's the same with unemployment. Unless the pandemic policies are perpetually maintained, then our current record low unemployment rate, which are the result of these policies, will go back to historically normal levels."

Even the RBA itself said these low unemployment figures won’t last despite its intentions. In the October cash rate decision, Bullock expected unemployment “to rise gradually” to around 4.5% late next year.

“Our actions of 2020-22 won’t be repeated again,” Sarris said. “We won't lock down and exacerbate build-ups of latent demand that then get deployed via revenge spending. We won't likely have near zero interest rates again. We won't have government cash handouts at enormous volumes again.”

With the RBA in the unenviable position of balancing the levers of the Australian economy, Sarris said we must temper our expectations when the unemployment rate goes back up.

“We can’t act like the sky is collapsing. If the media weren't jumping up and down when unemployment was in the 5's for extended periods of time pre-Covid, they shouldn't do so this time round as unemployment naturally trends back up,” Sarris said.

However, Sarris admits that all eyes are on the Reserve Bank to see how it manages its balancing act.

“Unemployment in the 3% range is inflationary in the backdrop of the disappearance of supply shock led inflation. Wage-led inflation is the scary one as it leads to spirals – and that always ends in a lot of pain.”

Get the hottest and freshest mortgage news delivered right into your inbox. Subscribe now to our FREE daily newsletter.