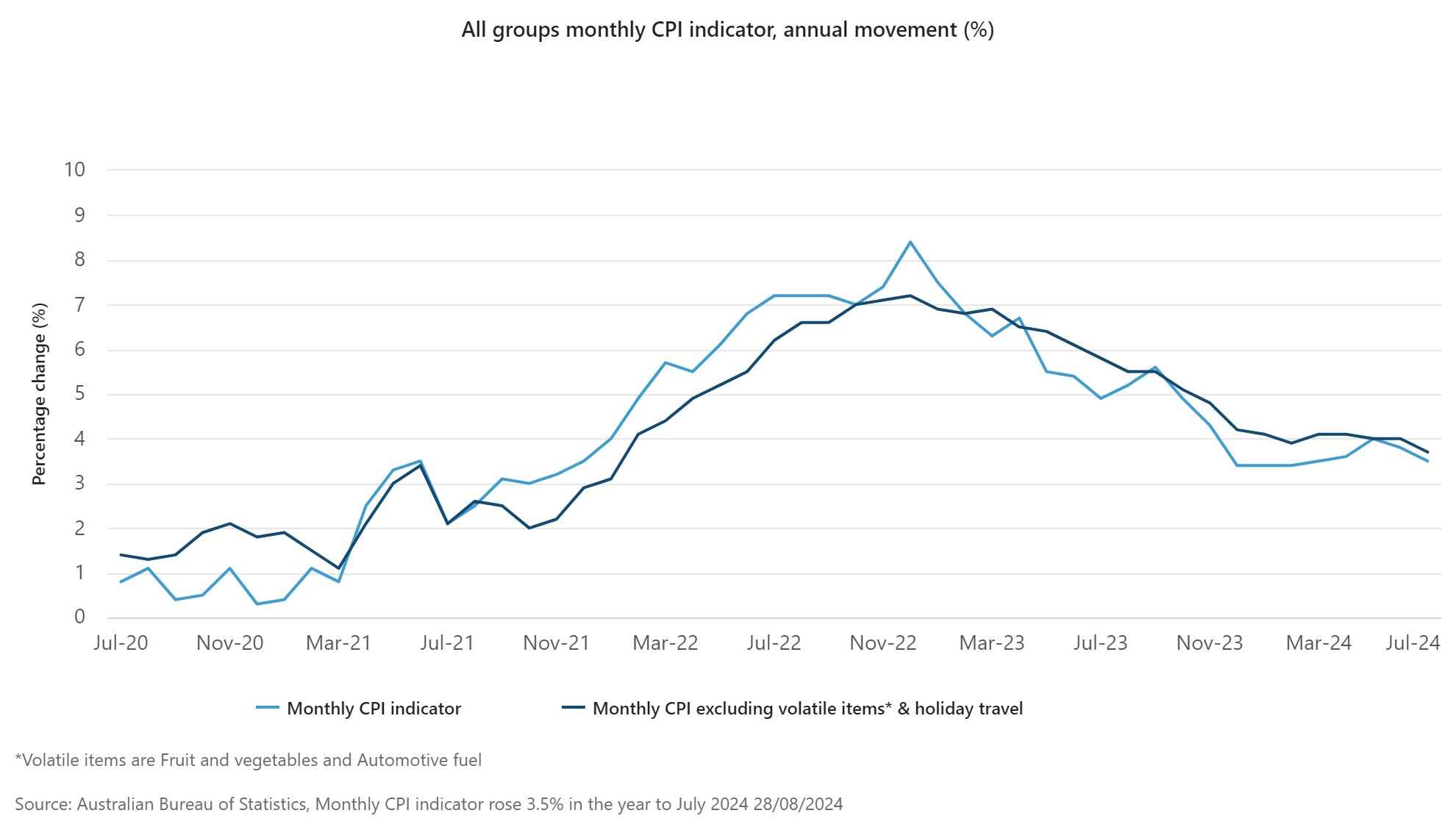

As Australians continue to grapple with the rising cost of living, the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) data offers a glimmer of hope. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has reported a decline in inflation from 3.8% in June to 3.5% in July 2024.

It comes after inflation had a small increase over the June quarter, which met the market’s expectations.

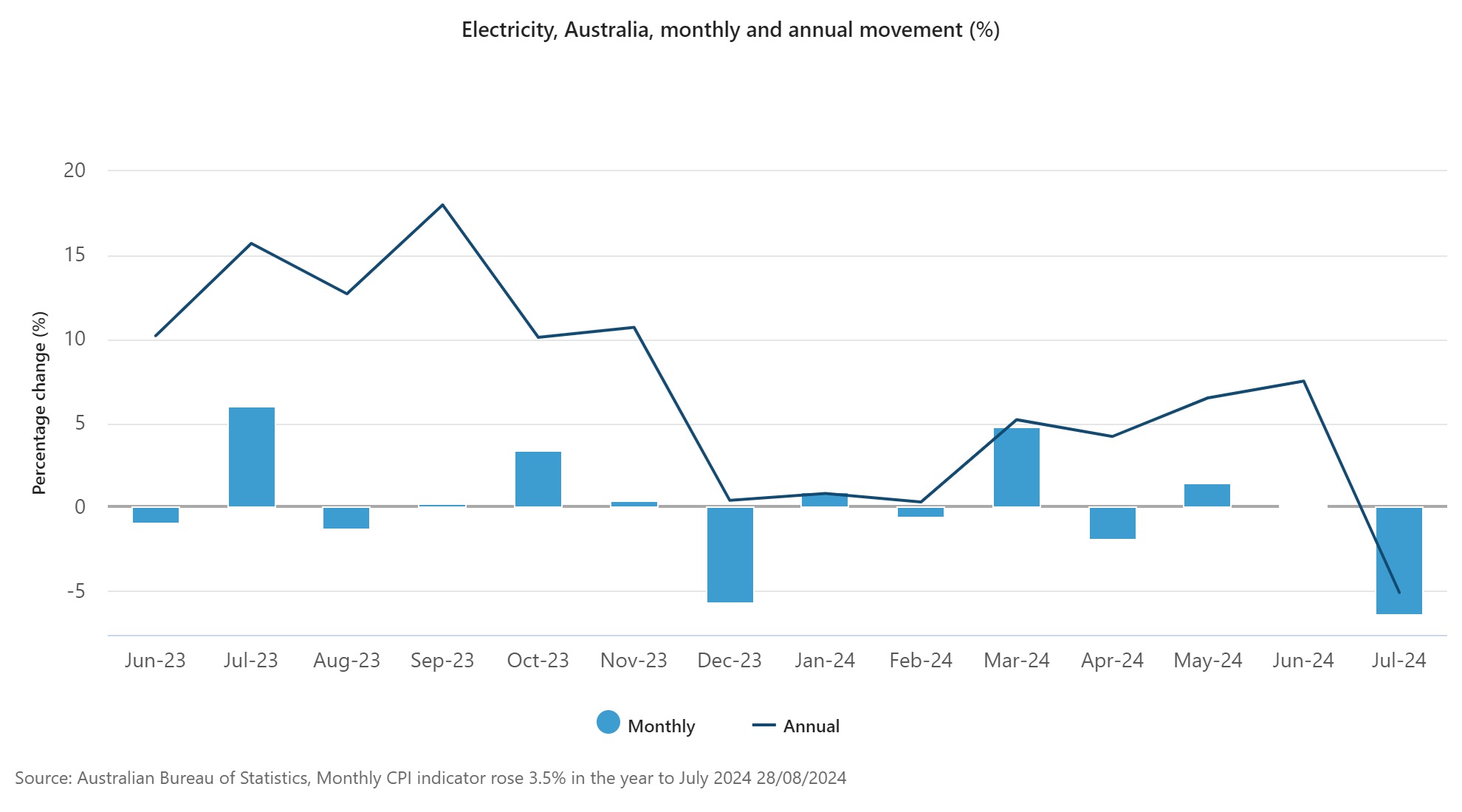

A key driver of this decline? Government electricity bill subsidies.

These rebates acted as a temporary circuit-breaker, providing some relief to households struggling with soaring energy costs.

However, some economists remain cautious. They argue that while these subsidies may have addressed the immediate symptoms of inflation, they may not have tackled the underlying causes.

The introduction of new Commonwealth and State rebates significantly impacted electricity prices, leading to a 6.4% drop in July.

Leigh Merrington, ABS acting head of prices statistics, said the first instalments of the 2024-25 Commonwealth Energy Bill Relief Fund rebates began in Queensland and Western Australia from July 2024 with other States and Territories to follow from August.

“In addition, State-specific rebates were introduced in Western Australia, Queensland and Tasmania. Altogether these rebates led to a 6.4% fall in the month of July,” Merrington said.

Without these rebates, electricity prices would have actually risen by 0.9% in July.

Economist Chris Richardson (pictured above) said that while the state and federal subsidies lower costs for families, he doesn’t think it means much for the Reserve Bank and interest rates.

“Economists talk about the role of central banks such as the Reserve Bank in keeping inflation low and stable. So surely a big drop in measured inflation is important?” Richardson said.

“But in many ways what economists really mean is that the RBA has a role in keeping the two side of the economy in balance – how much we spend versus how much we produce.”

Richardson said inflation starts when there is “too much money chasing too little stuff” – meaning that the economy is out of balance, with demand greater than supply.

“But the various new subsidies add to the amount of money that can be spent, so they add to demand while not adding anything to supply.”

Essentially, it means that subsidies are much better at rearranging cost of living pressures than they are at reducing them.

However, Richardson said there are also two arguments worth noting that do say a big burst of taxpayer money can help fight inflation:

The momentum argument is that subsidies can be a circuit breaker, according to Richardson – where lowering inflation can itself further lower inflation because a bunch of things (such as government payments to the states or to the unemployed) are indexed.

“That’s true, but it also isn’t huge – it’s a bit of a ‘pulling yourself up by the bootlaces’ argument,” Richardson said.

The second argument is one around expectations.

Inflation might start because there’s too much money chasing too little stuff, but it can keep going simply because workers and businesses think it will.

“A bunch of businesses use inflation as a bit of a benchmark when they announce price increases. And it’s similar with wages – what workers chase is partly linked to the costs they face,” Richardson said.

“That’s why subsidies can help the inflation fight when it’s at its toughest – because they can help to reset expectations.”

Of course, electricity price is just one component of Housing, which, in turn, is just one segment used to measure CPI.

On an annual basis, Housing rose 4.0% in the 12 months to July, down from 5.5% in June. Rents increased 6.9% for the year to July, down from a rise of 7.1% in the 12 months to June, reflecting continued tightness in the rental market in capital cities.

The annual rise in new dwelling prices has remained around 5.0% since August 2023, with builders passing on higher costs for labour and materials.

Annual inflation for Food and non-alcoholic beverages was 3.8% in July, up from 3.3% in June.

The largest contributor to the annual rise in food prices was Fruit and vegetables, which rose 7.5% in the 12 months to July, compared to 3.6% to June.

Higher prices for strawberries, grapes, broccoli and cucumber drove Fruit and vegetable prices to their largest annual rise since December 2022.

What this shows is that while Housing may have been provided a circuit breaker in the form of subsidies, other segments are still rising and therefore still putting pressure on the cost of living of Australians across the country.