Amidst soaring rents and dwindling availability, a staggering number of homes across Australia remain unoccupied, including 873,488 used as secondary residences and 13 million spare bedrooms.

This paradox poses a critical question: Can these empty spaces offer a solution to the growing housing affordability crisis, particularly in hard-hit regions such as Sydney and Melbourne?

While housing shortages are a global concern, property expert Ritesh Tandon (pictured above) said the existence of vacant homes in a country with a growing population raised questions about the efficiency and accessibility of Australia's real estate market.

“The impact of empty houses on the Australian community is multifaceted,” said Tandon, founder of Melbourne-based buyers agency Nest or Invest. “Firstly, it contributes to the widening gap between the property haves and have-nots.”

“The dream of homeownership, once considered a fundamental part of the Australian identity, is slipping away for many as housing prices continue to soar. This has socio-economic implications, as stable housing is a crucial factor in determining one's overall well-being.”

Australia’s vacant homes are not a new issue.

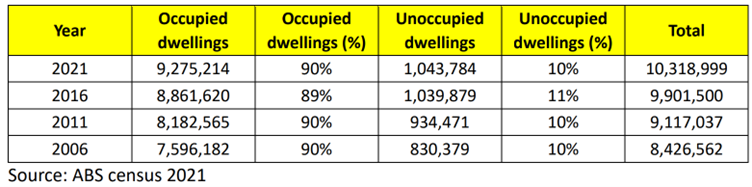

The 2021 Census reveals that 10.1% (1,043,776 homes) of Australia’s 10,318,997 private dwellings were unoccupied on the night of the Census.

Some 89% of the dwellings were in use as a primary residence, 9.7% were in use but not as a primary residence and 1.3% showed no sign of recent use.

This trend hasn’t changed since 2006 wherein the average unoccupied dwellings remain around the 10% mark.

Around 10% of dwellings are always empty in Australia

While this may seem that a very large proportion of Australia’s housing is unlived in, the reality is dwellings are identified as unoccupied for several reasons.

According to Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, top reasons for a dwelling to be unoccupied are:

1. Homes are being renovated

2. Homes being sold, up for sale or awaiting transfer

3. Newly built or bought homes where no one has moved in yet

4. Rental homes awaiting new tenants

5. People living away temporarily from home during the census count (travelling or visiting other homes)

6. Homes are deemed unliveable

7. Deceased estates or properties inherited through wills or family estates may remain unoccupied due to disputes among inheritors.

8. Holiday homes

9. Homes owned by people currently living overseas

10. Homes being land banked, that is held vacant until the local area economics (or personal circumstances) make it more profitable to sell or redevelop the property.

“Other reasons being the rise of short-term rental platforms like Airbnb,” said Tandon. “Shifting demographics, such as population decline in certain areas or changing community dynamics, can lead to houses being left empty as demand for housing decreases in particular regions.”

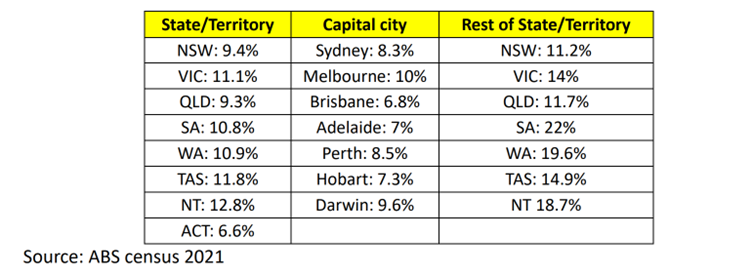

The prevalence of empty houses is not evenly distributed across the country.

Amongst the states and territories, Northern Territory had the most unoccupied dwellings at 12.8%. Melbourne was the top capital city at 10%. Regional Western Australia and South Australia had the most unoccupied dwellings with 19.6% and 22% respectively.

Level of unoccupied dwelling across Australia

The number of houses in use as a primary residence were analysed using Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP) figures sourced from the ABS.

These are the houses that are assigned as the usual residence of at least one person in the population snapshot on June 30, 2021.

Map of primary residence in use across all local government areas in Australia

Note: Colour indicates the percentage of houses used as a primary residence. For example, a circle shaded dark red indicates that more than 92% of houses in the area are used as a primary residence, while a circle shaded yellow indicates that less than 80% of houses in the area are a primary residence. Circle size indicates the number of houses in the area. Areas with larger circles have a higher number of houses relative to areas with smaller circles. For the full interactive map, click here.

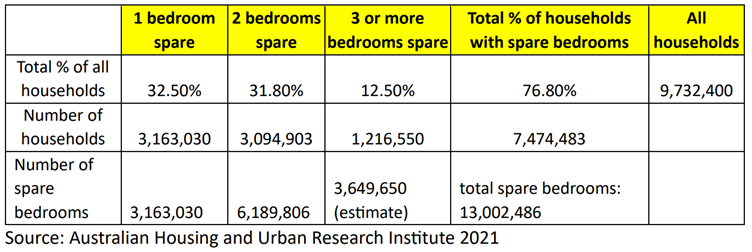

Despite Australia's uneven distribution of housing, a deeper inefficiency lies within individual homes – millions of unused bedrooms.

An analysis of the ABS survey on Income and Housing revealed that nearly 76.8% of households, totalling around 7.4 million, reside in homes with surplus bedrooms, resulting in approximately 13 million unused sleeping spaces.

These extra rooms, while not used for sleeping, play crucial roles such as home offices and recreational areas.

Moreover, AHURI research indicates that older homeowners are more likely to have spare bedrooms, particularly in the 55–64 and 64–74 age groups.

To address this, new laws designed to encourage pensioners to downsize their larger homes had been introduced, offering a 24-month assets test exemption and significantly lowering the deeming rate.

Number of private dwellings with spare rooms

With the issue well documented, it’s clear governments know about Australia’s empty houses and rooms and as evidenced above, have moved to address the issue.

However, Tandon criticised some policies saying they didn’t go far enough.

For example, the Victorian government introduced various taxes to help address the lack of housing supply in Victoria.

“Vacant residential land tax is the one introduced by the State Revenue Office but only applies to vacant properties under 16 councils in the inner and middle ring suburbs of Melbourne out of total 79 councils in Victoria,” Tandon said.

“Moreover, there are exemptions to it meaning if the property was used as a holiday home and occupied by the owner for at least four weeks of that year, they don’t pay the above tax.”

Therefore, despite having deterrents in place, Tandon said the tax policies don’t seem to be overly effective and ignore 80% of the state jurisdictions which seem to be having most of the vacant properties.

“Homeowners with spare bedrooms must pay income tax on the rent received from the tenants leasing the rooms,” Tandon said.

“For pensioners, this might mean the amount they receive as rent reduces their pension amount. For these reasons, many people avoid considering renting out a room, continuing the problem.”

Millions of unused bedrooms and empty houses cast a long shadow over Australia's housing crisis.

Beyond the individual cost to those struggling to find affordable homes, it raises questions about equity and efficient land use.

To tackle this complex issue, Tandon shared some potential solutions:

Tax incentives for renting spare rooms

“Moreover, the scope for vacant residential land tax will have to be expanded to all properties across the state,” Tandon said.

The prevalence of empty houses and rooms in Australia is a complex issue with far-reaching consequences. It challenges the traditional notion of homeownership and highlights the need for thoughtful urban planning and policy interventions.

“Balancing the interests of property investors with the housing needs of the broader community is a delicate task, but addressing this silent crisis is crucial for creating a more equitable and sustainable future for Australia,” Tandon said.